Hello readers! Today’s post is the first in what I hope to be an ongoing series. I have been working on it for a while now, so I hope you guys like it. In these problematic authors’ posts, I will pick one or two authors, read (or reread) some of their books, and share my thoughts on the problematic elements with you here.

I decided to go for an author with whom I am very familiar, and most of you will be as well: Dr. Seuss. In these posts, I’d like to talk a little about the authors, the harm in their books, a bit about adaptations and their depictions of the harmful elements, if that applies, and my thoughts on everything.

This series isn’t about telling you what you should or shouldn’t read. Everyone has to make their own decisions and decide what’s appropriate for themselves or their kids, if applicable. This is just my opinion on when separating art from the artist works for me, when it doesn’t, and how the age of the audience changes my perspective.

I’d love to talk in this series about different types of problematic elements. For example, racism, sexism, graphic violence in children’s books, and other things. The idea is to focus on authors whose books have problematic elements inside them, not just authors who have done something outside of their books, as I wouldn’t need to read their books to talk about what they’ve done.

Let me know if you have an author you’d like me to feature! I have quite a few ideas written down, but you might have something in mind as you are reading, and I’d love to hear it.

Dr. Seuss is a beloved author for me and many others. When I was a kid, I memorized the entirety of One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish before I could even read.

Honestly, it wasn’t until Dr. Seuss Enterprises chose to unpublish several of his books in 2021 that I became aware of the racism present in some of his work. I’ve mentioned this before, but I grew up in a sundown town. Before the age of twelve, I had very little interaction with people of color. I had a few distant cousins I saw occasionally, but there was no real non-white presence in my everyday life. Given that context, it’s not surprising that I didn’t recognize racist imagery or language in the picture books I grew up with.

Thinking back, I don’t remember reading any Seuss to my daughter when she was that age. I do remember reading her picture books, but they were usually ones from the library featuring characters she already knew. I do remember reading her a few of the Magic School Bus and Little Critters books, but not Dr. Seuss.

Of the 6 books that are no longer being published, I had only read 3 of them before, and I still own my copies. Does anyone else have all their picture books from childhood still, or is that just me? Those six titles include And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer.

Dr. Seuss was born in 1904 in Massachusetts, during the height of the Jim Crow era and the Chinese Exclusion Act. This context does not excuse what we’ll discuss later, but it does help explain the cultural environment in which his early work was created.

Seuss was the person I wanted to start with because he is different from most authors with problematic books. He did later have some regret for what he wrote and changed some of the book’s racist imagery, which I will also show in this post.

His first published book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937), follows a boy named Marco as he walks home and imagines an increasingly elaborate story of what he’ll tell his father he saw along the way.

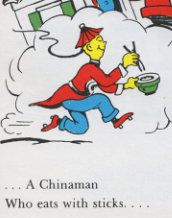

The most glaring issue I noticed upon rereading the book was the depiction of a stereotypical Chinese man running alongside the parade while holding chopsticks

While researching this section, I learned that this was not the original illustration. In the original version, the character was depicted with yellow skin. This stood out to me immediately, as none of the other characters in the book are given a specific skin color.

Additionally, the text originally used the term “Chinaman” rather than “Chinese man.” At the time, this term was commonly used to dehumanize Chinese people and is now recognized as a slur. Given that context, it’s easy to understand why the image and language were first altered and later why the book was ultimately removed from publication altogether.

However, I can’t give Seuss too much credit for doing this, as it was the only illustration in any of his books that was changed. There are worse ones in a book we will talk about a little later.

McElligot’s Pool was Dr. Seuss’s fifth book, published in 1947, ten years after his debut. It’s also the only book in which Seuss used watercolor illustrations. Because of budget restrictions at the time, roughly half of the book is printed in black and white.

I hadn’t noticed this until rereading it for this post, but Marco, the same boy from And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, is also the main character here. Once again, Marco’s imagination takes over as he waits by a pool, imagining the incredible creatures that might live beneath the water’s surface.

Like Mulberry Street, McElligot’s Pool relies on stereotypical depictions of real-world cultures. In this book, Seuss includes caricatured portrayals of Eskimos and Tibetan people. Notably, three of the six books that were later removed from publication contain similar depictions of Eskimos, suggesting that this wasn’t an isolated or accidental choice.

For a more in-depth discussion of these portrayals, and of the term “Eskimo” itself, I recommend reading THIS ARTICLE, which provides important historical and cultural context.

The next one I read for this post was If I Ran a Zoo, which was published in 1950. This one is by far the worst of the three mentioned so far. If I Ran the Zoo follows Gerald, who imagines how he would run the zoo he is visiting.

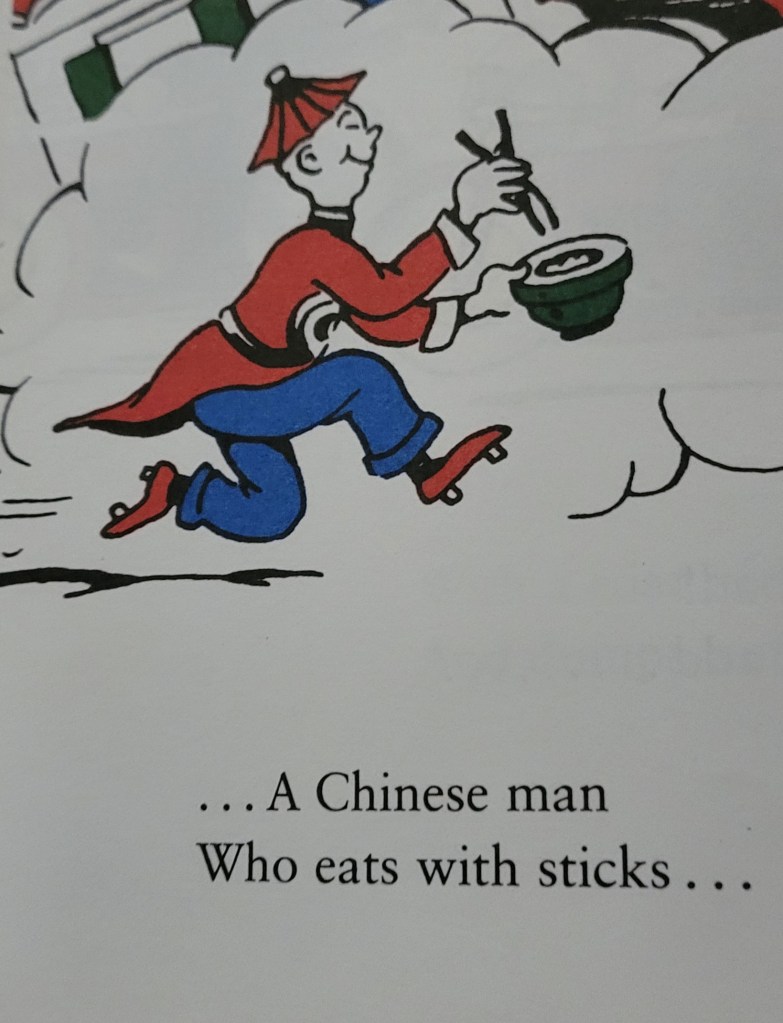

In this book, Seuss takes different human groups and uses them as inspiration for imaginary animals. The concept might have been far less harmful if he had drawn on animals native to those regions instead of caricaturing the people themselves.

The Chinese men are depicted stereotypically, are mentioned as having slanted eyes, and the animal being carried also has similar Asian-looking features.

African people are represented even more problematically. They are drawn to resemble monkeys and are shown with exaggerated nose piercings. Piercings hold deep cultural significance across many African cultures, making this depiction not only inaccurate but also disrespectful. African people and culture are also not a monolith, as it is a continent and not a country.

Other stereotypical depictions in this book include Persians and Russians. These depictions serve no narrative purpose and clearly contribute to the book being one of the titles later removed from publication.

Horton Hears a Who was published in 1954, and is widely regarded as a depiction of America’s occupation of Japan following World War II. Unlike his earlier works, this book demonstrates a marked shift in Seuss’s perspective. Horton, who insists that “a person’s a person, no matter how small,” can be read as a story about empathy, recognition, and the importance of respecting all people’s values that stand in stark contrast to the stereotyping found in Mulberry Street, McElligot’s Pool, and If I Ran the Zoo.

During this period, Seuss had visited Japan and even dedicated the book to a Japanese friend, suggesting that personal experience contributed to his evolving viewpoint. He also went on to publish other progressive works, including Green Eggs and Ham and The Lorax, which continued to emphasize fairness, inclusion, and social responsibility.

I also want to discuss The Cat’s Quizzer, published in 1976. By this time, Seuss had already begun revising earlier works, such as And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, to remove problematic imagery. I hadn’t read The Cat’s Quizzer before and didn’t have a copy, so I focused on the sections that have been widely discussed in articles about the book. I won’t link to where I found it online, as I’m not certain it’s legally available there.

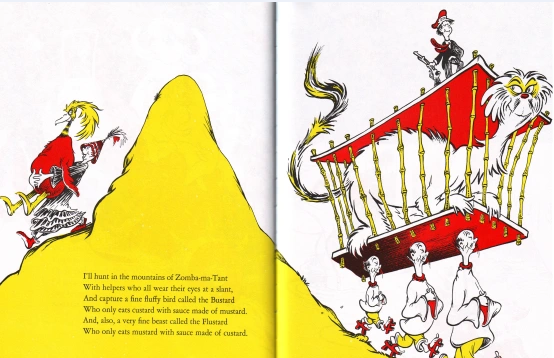

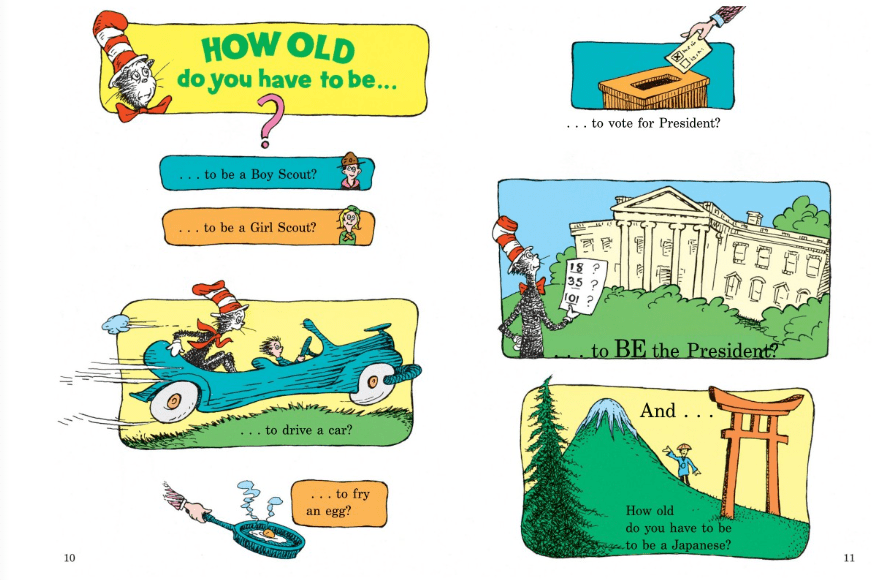

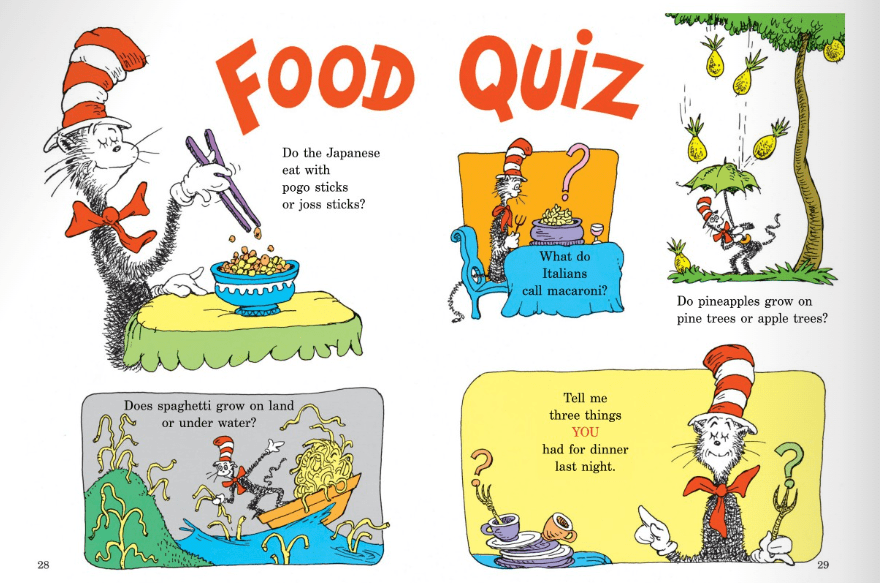

This book is mostly a collection of nonsensical quiz questions, but two of them mention Japanese people, which contributed to Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ decision to remove it from publication.

This page centers on questions of how old you have to be. The one that stands out the most is, “How old do you have to be to be a Japanese?” On the answer page, it says, “All Japanese are Japanese the minute they are born.” The wording feels strange and, to me, dehumanizing. Saying “a Japanese” reduces people to a category rather than acknowledging them as individuals. Using terms like “Japanese person” or “Japanese people” would have been more accurate and respectful.

On the Food Quiz page, the first question asks, “Do the Japanese eat with pogo sticks or joss sticks?” The answer page says, “Pogo sticks they jump on. Joss sticks they burn. They eat with CHOP STICKS.” While the answer is technically correct, the phrasing reinforces a cultural stereotype rather than presenting a neutral or playful fact. Including “chopsticks” in the question itself, instead of relying on a pun that frames a culture as amusing or a joke, would have been a small change that made a big difference.

Even after decades of growth in his work, Seuss still included language and imagery here that feel othering and insensitive. This is why, despite his earlier progressive efforts, The Cat’s Quizzer was removed.

Dr. Seuss changed many of his views over his lifetime, which is certainly a positive development. However, that doesn’t erase the harm present in his works, and he also made many more racist depictions outside of his books. While some of these issues can be understood in the context of their time, he was still an adult capable of learning better.

I’d love to hear your thoughts, both on Dr. Seuss’s work and on any other authors you think would make interesting subjects for this series. The next post will also focus on a children’s author, and I hope it will continue this conversation about how problematic elements in literature affect readers of all ages.

Be sure to like and subscribe so you don’t miss future problematic author posts!

Happy blogging and bookish adventures! 📚🦒✨

This post was created by Allison Wolfe for www.allithebookgiraffe.com and is not permitted to be posted anywhere else.

Where to find me: https://linktr.ee/Allithebookgiraffe

Add this user on Goodreads for all your trigger warning needs: https://www.goodreads.com/user/show/86920464-trigger-warning-database

Leave a comment